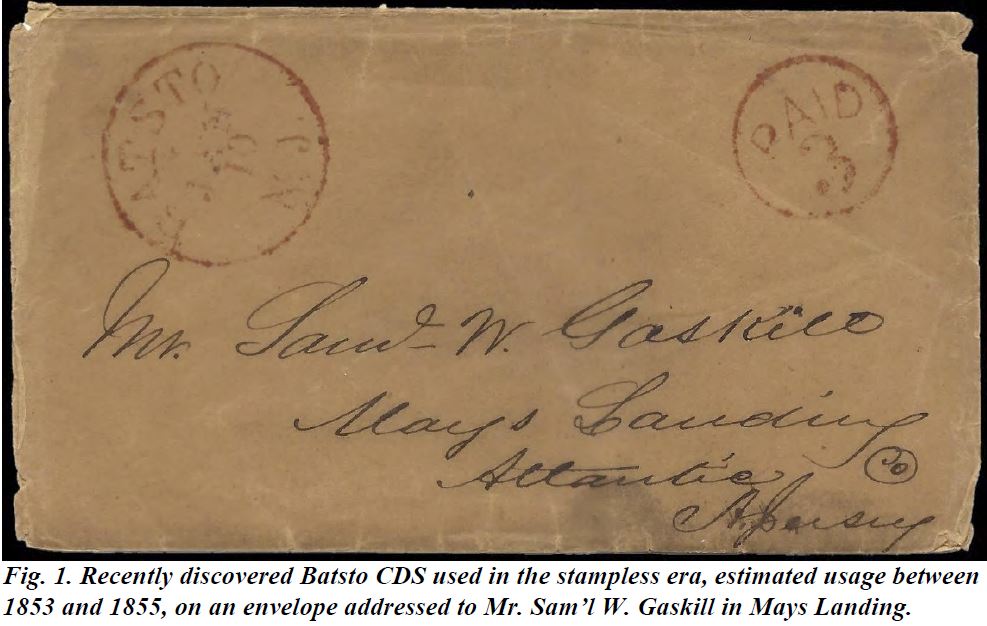

The cover shown in Figure 1 is the first reported example of the stampless-era Batsto, NJ

CDS. At NOJEX in 2013 I asked one of the cover dealers if he had any New Jersey covers, and

he replied that he only had a few, which he’d just acquired. This cover was on the top of the

small stack, where it stayed for all of about two seconds(!).

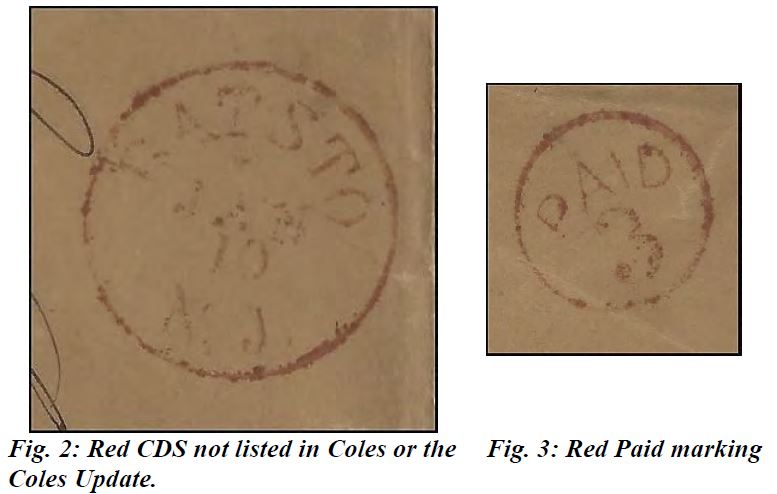

The red BATSTO JAN 10 N.J. CDS measures 30mm. The matching red PAID 3

handstamp measures 22mm. Closeups of each are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

The cover is not dated, but as the Batsto Post Office was opened June 28, 1852, and as

mandatory prepayment of postage by U.S. postage stamps was enacted in March of 1855, the

envelope would then date between 1853 and 1855.

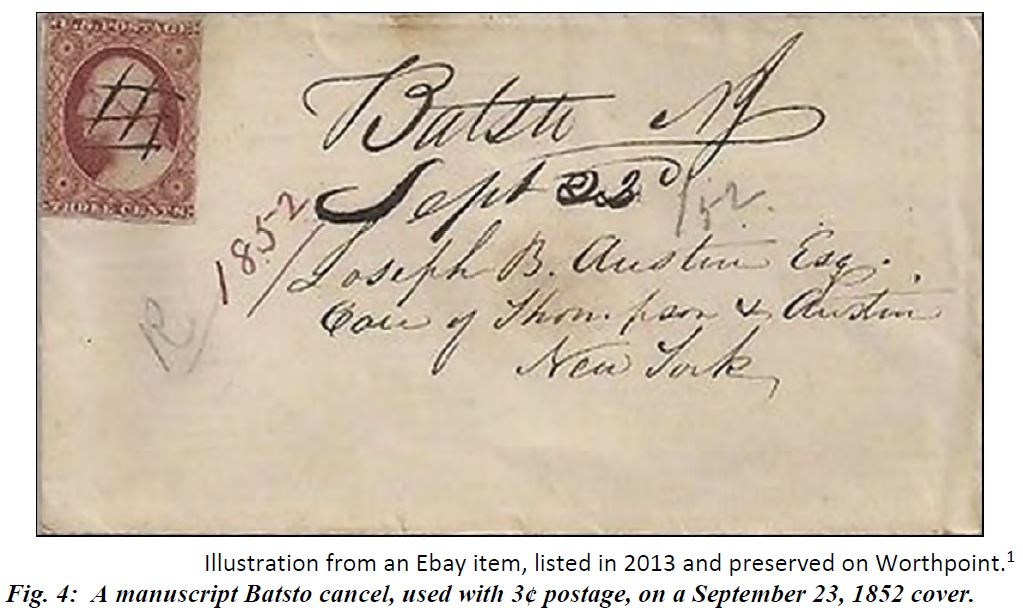

A manuscript BATSTO cancel on cover with a 3¢ 1851 stamp and docketed 1852 is

shown in Figure 4, it being sent only 3 months after the establishment of the P.O. and, of course,

predating the stampless cover as well.

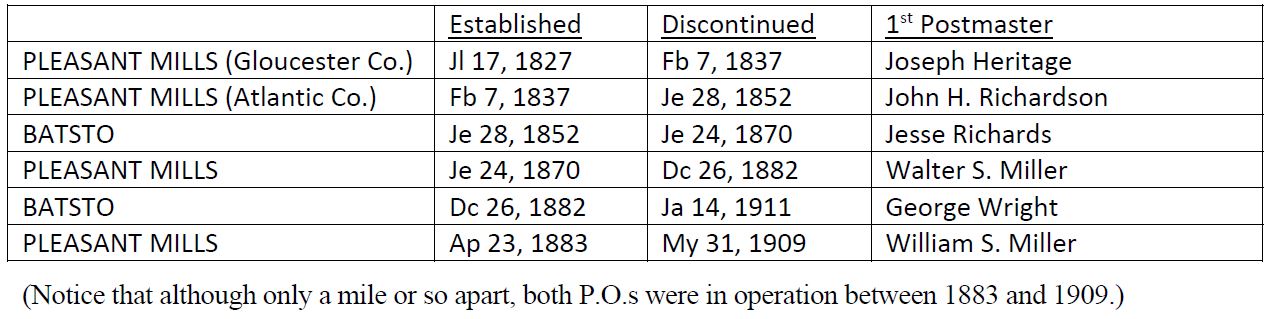

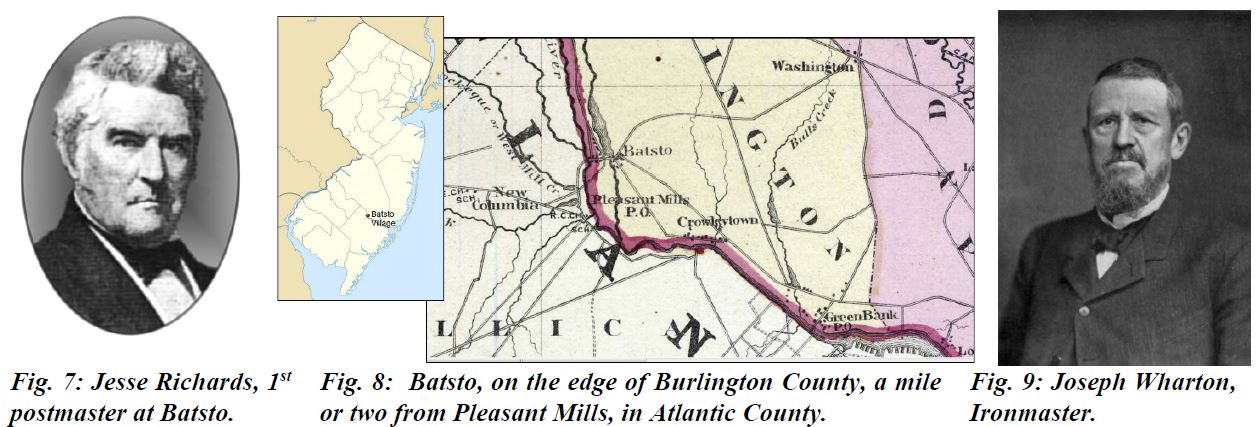

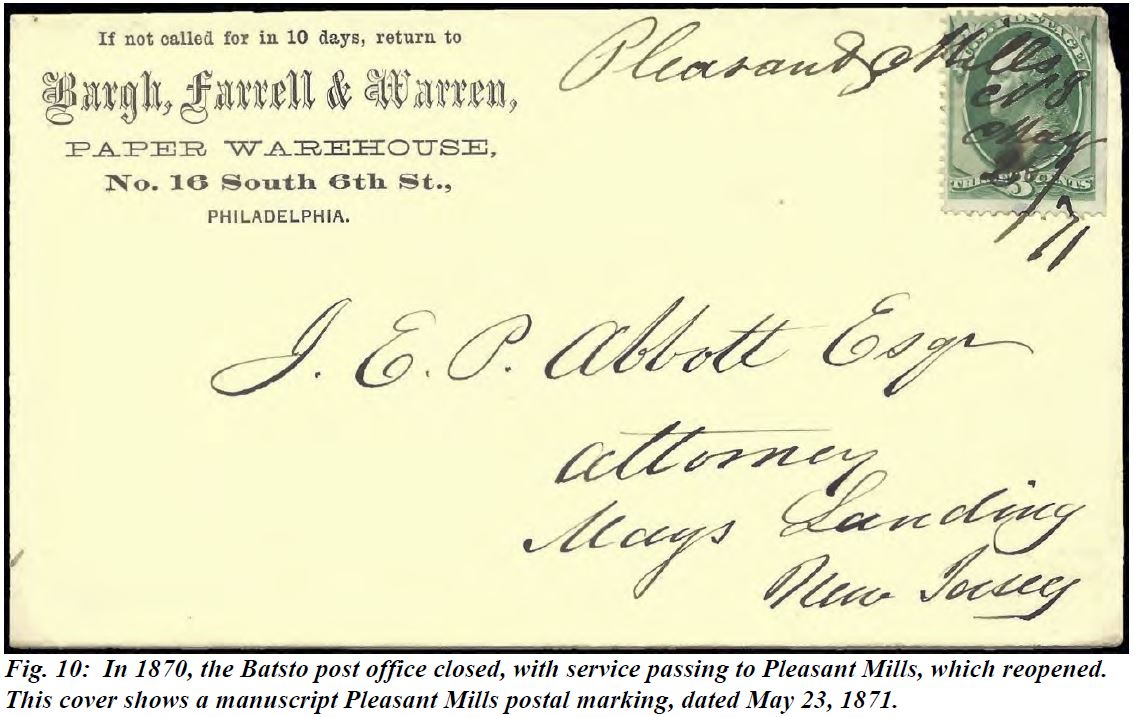

Batsto, Burlington County, and nearby Pleasant Mills, in Atlantic County, are only about

a mile or so apart, and thus have always been closely tied together, including the back and forth

establishing and discontinuation of post offices.

The area around Pleasant Mills was early on known as Sweetwater, and also as The

Forks, being at the forks of the Batsto and Mullica Rivers. During the Revolution, privateers

brought captured British ships to The Forks and nearby Chestnut Neck, and unloaded the cargo

to be sold at public auction. On Oct. 6, 1778, British troops attacked Chestnut Neck, raiding and

burning dwellings and whatever ships were there. Their intention was to then continue upriver

and destroy The Forks and the munitions-producing furnace at Batsto, but they retreated when

they were warned that Count Pulaski and his legion would soon be there to protect the area.

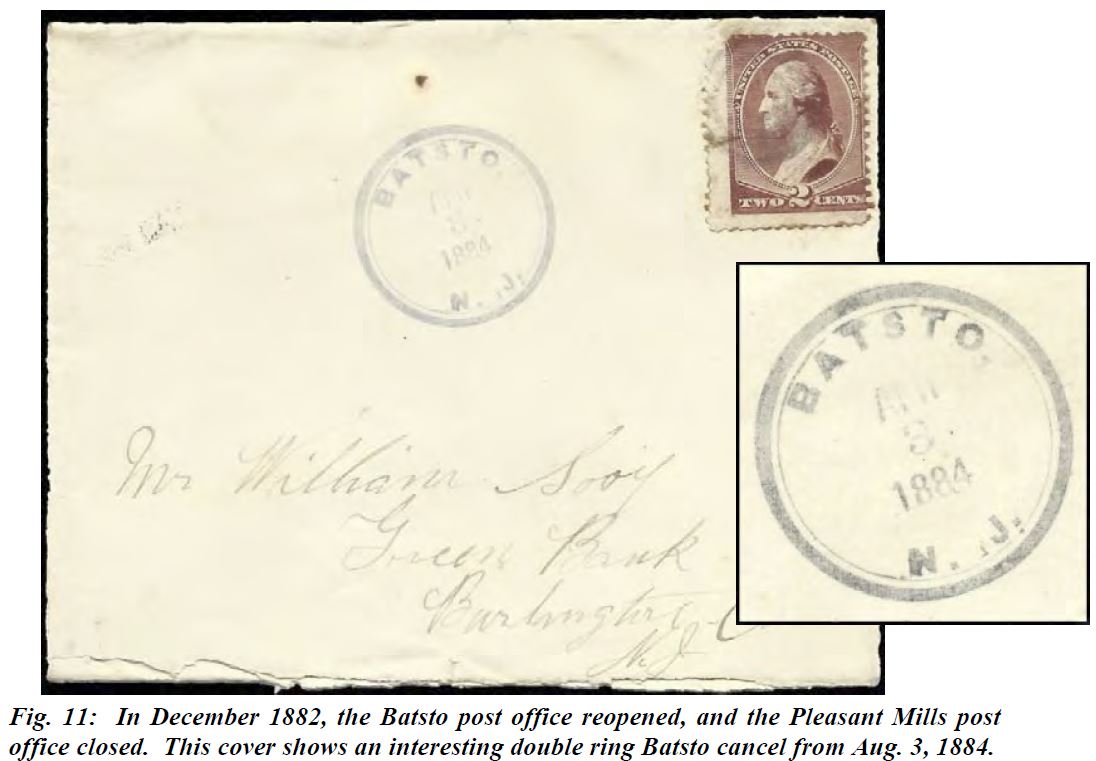

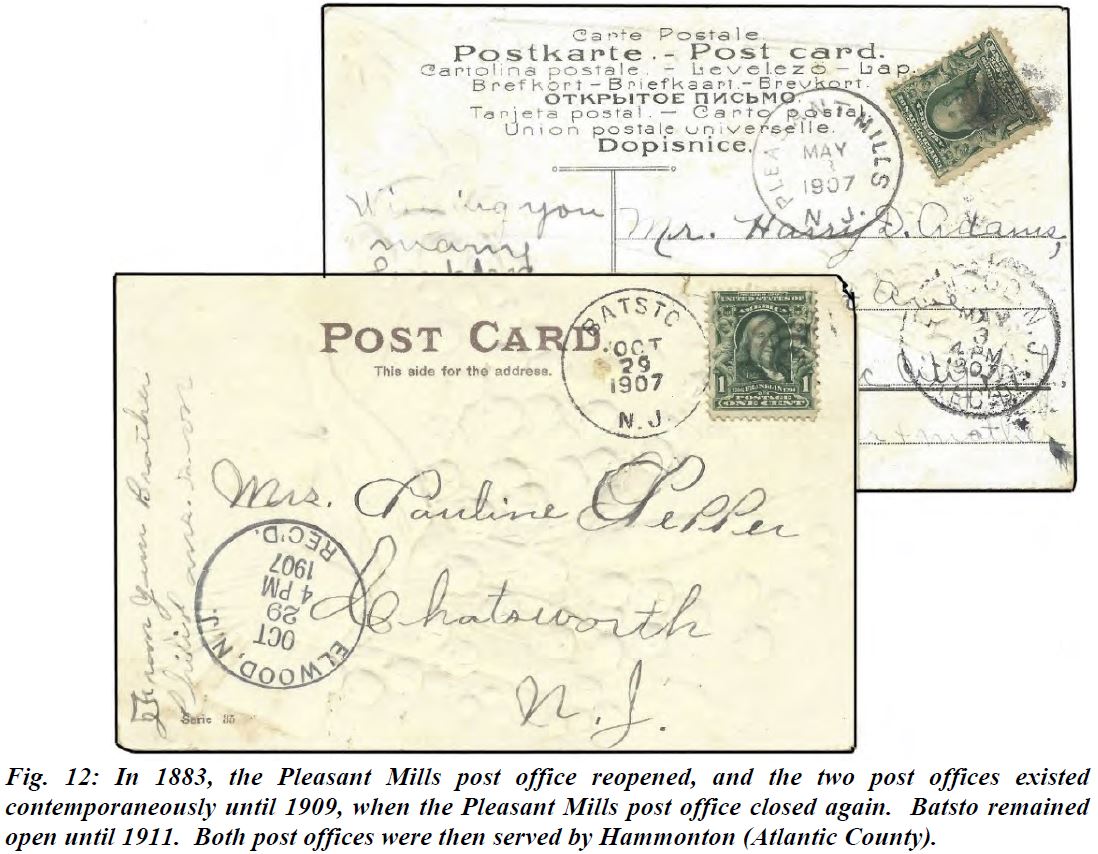

The establishment and discontinuation of the two post offices is as follows:

Batsto and its ironworks figure prominently in the colonial and revolutionary history of

southern New Jersey. This ironworks was one of a number of furnaces in the area which were

erected in the late mid to late 18th century and early 19th century, utilizing bog iron in the

manufacture of products. At one point there were 17 furnaces and as many forges scattered

throughout the Pine Barrens.

Located in Washington Township, Burlington County, in what is now Wharton State

Forest in the Pine Barrens, the tract of land on which Batsto was located had previously had

several sawmills, one possibly as early as 1739.

South Jersey legislator, merchant, and land speculator, Charles Read, bought the tract in

1766, and soon after gaining permission from the legislature to dam the Batsto River, built the

furnace at Batsto. Having also bought several other iron works, Read sold his share in Batsto

within two years to business partners.

Batsto was purchased in 1770 by Daniel Coxe and partner, Charles Thompson. Pig iron,

stoves, skillets, kettles and other household items were manufactured. During the American

Revolution, the furnace turned to producing cannons, cannonballs, as well as other iron products

needed by the Continental Army for the patriot cause.

In 1773, Coxe hired as Batsto’s manager William Richards, an eastern Pennsylvania iron

foundry worker who had five years earlier worked at Batsto for a year.

With the coming of the Revolution, Richards went back to Pennsylvania in 1775 to be

nearer the center of conflict, possibly spending the winter of 1778-9 at Washington’s camp at

Valley Forge.

In 1779, William’s nephew, Joseph Ball, who had come with him to Batsto in 1773,

acquired the ironworks along with two partners who were officers in the Continental Army.

Under his ownership, a forge was built, which enabled the manufacture of wrought iron

products.

William Richards returned to Batsto in 1781, and in 1784 became the owner, rebuilding

the furnace and erecting the mansion in the village. Under his ownership, the business prospered

and at one point the town had a population of over 500 people.

William Richards’ ownership continued until 1809, at which point he turned management

over to his son, Jesse. During the War of 1812 Batsto again produced munitions for the

American military.

With William’s death in 1823, the property was purchased by his grandson, Thomas S.

Richards, who retained his uncle, Jesse, as manager. Within six years, Jesse was a half owner of

Batsto.

By the middle of the 19th century, the South Jersey bog iron industry was in decline. The

natural stores of bog iron had been almost depleted by the 1820’s, and “the final blow to the Pine

Barrens iron industry came when richer ore and a more efficient fuel, in the form of coal, were

discovered in Pennsylvania”.2 Recognizing this, Jesse Richards built a window glass works at

Batsto in 1846, and a second glassworks in 1848, in which year the iron furnace went out of blast

for the last time. During the 1840’s there was also a brickworks at Batsto, as well as some

shipbuilding activity. (Capt.) Samuel Gaskill, to whom the Batsto stampless envelope is

addressed, was perhaps the most famous shipwright of Mays Landing.

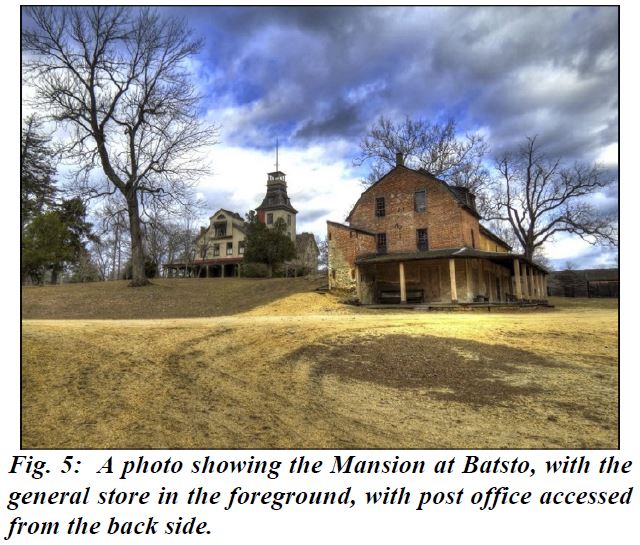

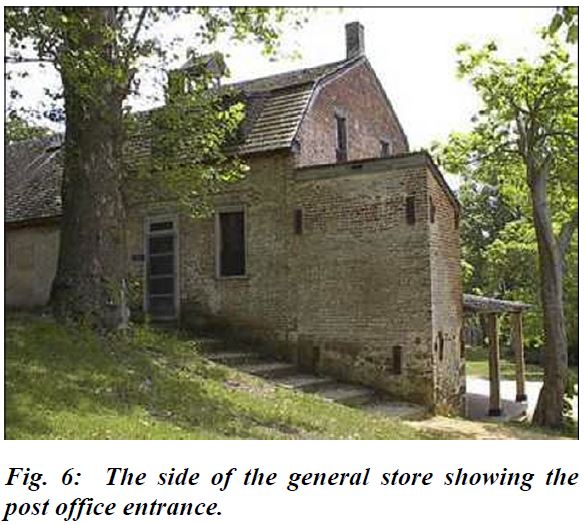

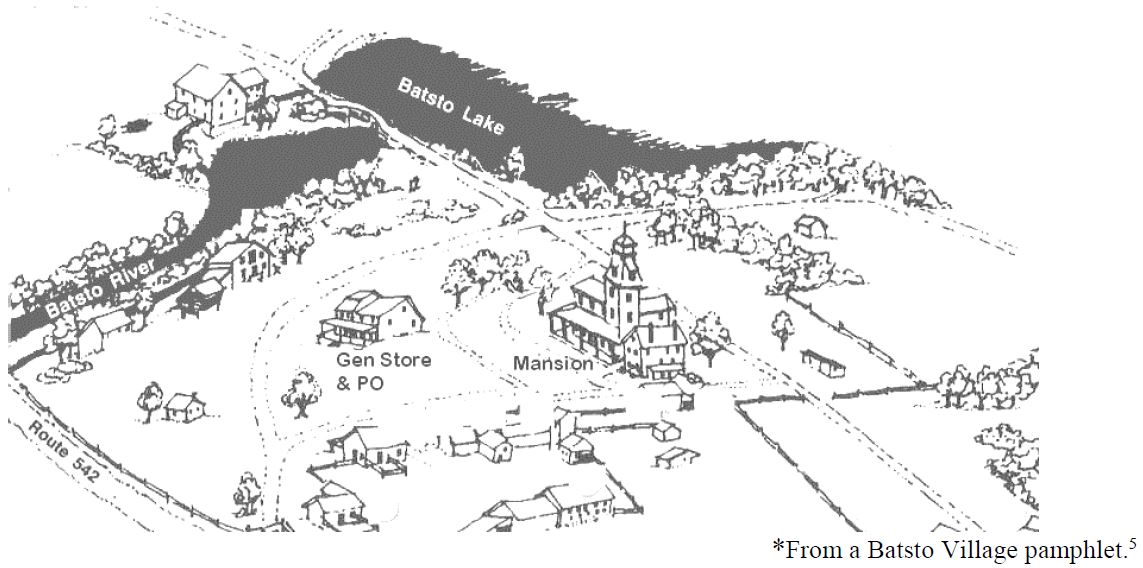

In 1852, during the peak years of the Batsto Glassworks, the town had a population of

375 people living in 75 houses located on six village streets. There was also in the village the

mansion, believed to have been built by the Richards family, a portion of which may have been

built before their ownership; the general store/P.O., the earlier section having been built prior to

the Revolution, and the western end built in 1846-7; the grist mill, which was built in 1828 and is

still in working condition; the blacksmith and wheelwright shops, both built around 1850; and

the sawmill (the present sawmill was built in 1882). The religious needs of the community were

served by the Methodist Church at the nearby village of Pleasant Mills, the church having been

built in 1808 on the site of a much older church.

Jesse Richards died in 1854 and was buried in the cemetery at the Pleasant Mills Church.

The Batsto Glass Works had operated successfully under his proprietorship. However, with his

death, ownership went to his son, Thomas H., who was more interested in politics and public life

than in industry.

The Glass Works started to decline. Workers also began to demand cash rather than store

credit as per the company town system. An anticipated railroad line never materialized.

Workers moved elsewhere and the houses in the village began to fall apart. Thomas Richards

had tried to prevent bankruptcy by selling off parcels of land, but by 1868 industry at the town

had come to a standstill, and Batsto went into receivership. A fire in 1874 destroyed what was

left of the furnace and glassworks, and consumed 17 of the workers’ houses.

Joseph Wharton, a Philadelphia industrialist, bought the property two years later for

$14,000. Wharton was buying up large parcels of property in the Pine Barrens with the idea of

damming its rivers and streams in order to create large reservoirs from which he could pipe water

to sell to the city of Philadelphia. The New Jersey legislature then passed legislation prohibiting

water being sent out of state. Wharton then concentrated on agriculture and livestock on the land

he had bought in the Pines.3

By the time Wharton died in 1909, he had accumulated 112,000 acres in the Pine

Barrens. In 1912, his heirs attempted to sell the land to the state of N.J. for $1 million, but the

state declined.4

In the early 1950s the U.S. Air Force tried to establish a gigantic jetport supply depot on

17,000 acres surrounding Batsto. At this point, the state recognized the potential of the Wharton

tract, and began to make efforts to buy the land. In 1956, the state bought 96,000 acres for $3

million, and Wharton State Forest came into existence – the largest State forest in New Jersey,

encompassing some 115,000 acres of Pine Barrens land. Within a year an extensive restoration

project had been launched for the historic village of Batsto.

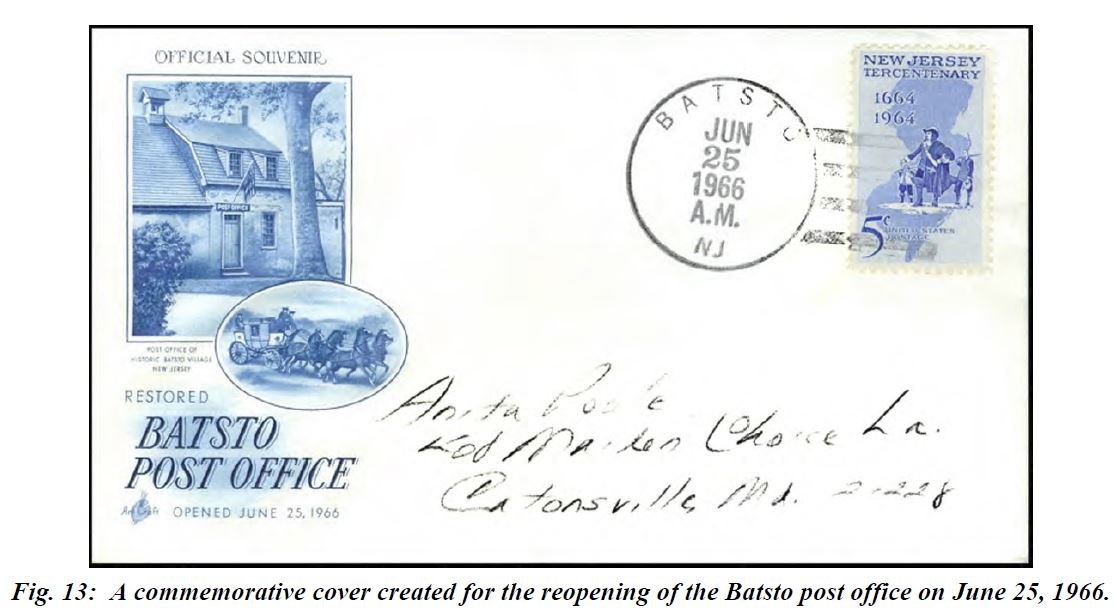

That project included preservation of the Batsto post office there as well. It was restored

and reopened in 1966, and still acts as a post office today, as a rural station of Hammonton. It

has no zip code, in keeping with its historic nature, and mail is hand cancelled.

It is now possible to visit this village in its restored state. For more information and

directions, go to: http://www.batstovillage.org/

For those who would like to learn more about the history of Batsto, the Richards family,

and the furnaces, forges and bog iron industry of the Pine Barrens region, information is

contained in a number of publications. Some of these sources are:

- Beck, Henry Charlton, Forgotten Towns of Southern New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers U. Press,

1983.

- Beck, Henry Charlton, More Forgotten Towns of Southern New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers U.

Press, 1963.

- Beck, Henry Charlton, Jersey Genesis: The Story of the Mullica River, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers U.

Press, 1983.

- Boyer, Charles S., Early Forges and Furnaces in New Jersey, Univ. of Penn. Press, 1963.

- Pearce, John E., Heart of the Pines: Ghostly Voices of the Pine Barrens, Hammonton, NJ: Batsto Citizens

Committee, 2000.

- Pierce, Arthur D., Family Empire in Jersey Iron: The Richards Enterprises in the Pine Barrens, New

Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers U. Press, 1964.

- Pierce, Arthur D., Iron in the Pines: The Story of New Jersey’s Ghost Towns and Bog Iron, New

Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers U. Press, 1957.

- Solem-Stull, Barbara, Ghost Towns and Other Quirky Places in the New Jersey Pine Barrens, Medford,

NJ: Plexus Pub., 2010.

|